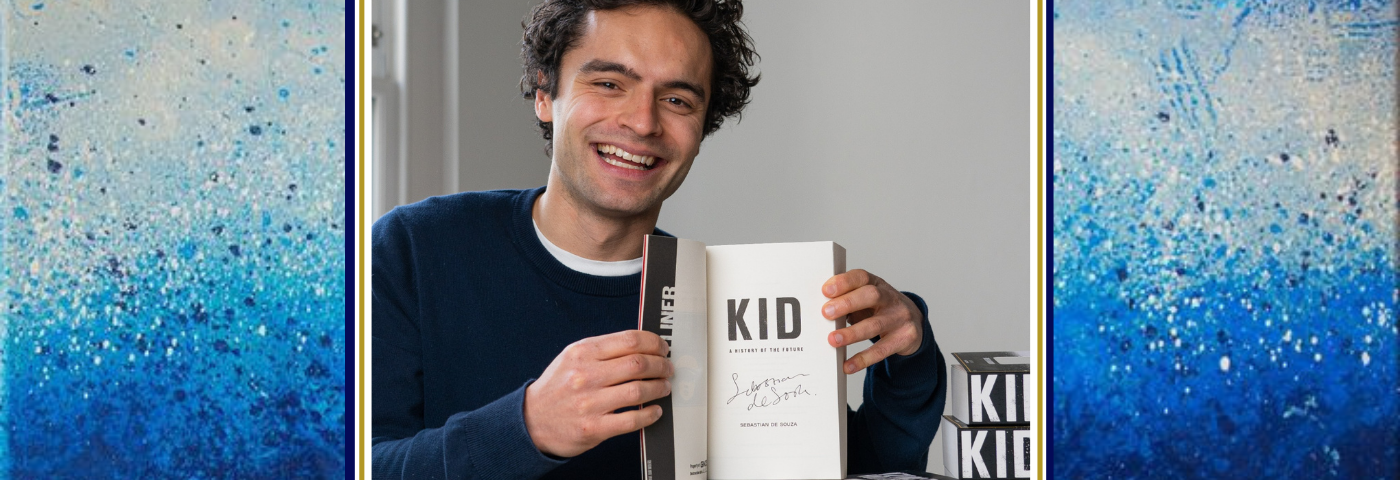

An exclusive extract from Kid: A History of the Future by Sebastian de Souza

Chapter 1 – Champagne Supernova

I’m definitely coming up. They must be too. The CD in my Walkman skips a little before finding itself again. Liam Gallagher singing about a champagne supernova and being caught beneath a landslide . . . The Roxi hits just in time for the chorus. Timed to perfection. I look to the others on either side of me, our jackets tagged up with badges and other miscellaneous tat we’ve found in the Ghetto over the years; each of our pairs of jeans more shredded than the next; me with my red scarf flying. Walking all in a line, bopping our heads, jamming to Oasis. I’d love to know how many people listen to Oasis these days, let alone Britpop, let alone music. The smile leaves my face.

We’re out of place. Weird. Just how we like it. Well, we would look weird, if there was anyone else around to see us.

Everything’s changing colour, my legs are getting lighter. It’s what happens when you take more Roxi than you’re supposed to. More than one pellet of this stuff will get you high as a kite. I do a 360; the Circus is empty this morning, from the Wall to the desolate streets running away south and east. Not unusual, but always disappointing.

Eliza’s eyes have gone from their usual bright green to a kind of metallic grey and her pupils are dilated. Pascale just won’t stop smiling and, yeah, there it is again – his famous bear hug.

Jeeeeeeeeesus. I’m high as a kite. It never fails to amaze me how, if you take a tiny bit more than you should and pair it with a great song, you can totally change the way things look. Change the world. If only it was that simple, I think.

It’s a bright day, not sunny, but that’s no surprise as it’s hardly ever been blue in my lifetime. It’s an ugly shade of brown, but a bright brown, an aching kind of brown that hurts your eyes if you look up for too long. I guess the sun is throbbing away somewhere behind the soot and the ash and the mud, but I can’t see it. That’s where the Roxi comes in. Take just a pinch more than you should and the seemingly impossible happens – it makes the rubble and dust turn back into the jostling crowds of buildings they once were, and all the ghosts of the Ghetto suddenly seem to come alive once more. It’s like going back in time, especially with the music blaring in your ears. The statue, holding its bow and jauntily standing on one foot with its wings spread, must be just about the only thing in Piccadilly Circus that looks the same as it did before the Flood. But right now I feel like I’m walking through London during the Golden Dusk, the time when people walked these streets freely, when people lived in the real world. Before the Upload when everyone cocooned themselves in haptic rigs, logged in, and the world went silent.

Scavving like this – the Walkmans, the uniform, the squad – means we can turn a totally lousy situation into a kind of game. Everyone in the Cell knows when Eliza, Pas and I are on duty – when it’s our turn to bring home the bacon – because we make an event of it. The others must think we’re such arseholes as we snake round the statue of Anteros, on our way up into Soho, Pascale dancing like an idiot, Eliza tripping like she’s a fairy.

It’s been like this since the first time we were sent out into the Circus on scavenger duty. Aged twelve. Six years on, we’re still a unit, a squad, the Scav Squad. It’s the name of our band too. Pas on drums, Eliza on guitar, me on keys and vocals. I love music, we all love music. I write the songs and the three of us jam together in my dorm room. My mum left me some manuscript paper to write the songs down. I’ve got an upright acoustic piano, a Kawai, which I scavved years ago from Ronnie Scott’s, an old jazz club on Frith Street. My prized possession. It’s suffered a lot – cigarette burns on the keys, pale circles bitten in the polish by the bottoms of whisky glasses, a few bashes from when we hauled it down here. I often wonder how long it had been there at the club, and who used to play it, back in the Dusk. Sitting at those keys and singing my songs with my best friends, I’m happy. I can forget.

Scavving is a dangerous job and scavvers come and go. We don’t. We started earlier than most and we’re the only ones who’ve stuck with it more than a couple of years. I suppose not having any parents is part of it – no one to cry when you run out of Roxi and end up dead in some alley.

We pretty much wear the same clothes every day. I don’t own a second pair of jeans and I’ve never gone a day without wearing my Harrington jacket, blue canvas with tartan lining. It belonged to my mum when she was my age – luckily she was tall and I’m pretty skinny. She was wearing it when she met my dad; at least I think that’s how the story goes.

All us youngers are expected to scav – running errands, finding food and other supplies. We congregate in my dorm beforehand with our Walkmans and our Roxi disps, just before Mungo comes doing rounds, so we have some time to prepare. First we pick a song from my record collection. I say ‘record’ but really what I mean is CD. I’ve searched and searched for vinyl but I’m pretty sure actual LPs were considered prehistoric in the early 2000s, so by the time the Flood came around and the Upload happened, they must have all gone. Disappeared into thin air, along with the rest of everything that was beautiful about the Golden Dusk.

I mean, I know CDs were pretty much over by the end of the Dusk, and everyone just streamed music on their phones, but now Streeming is strictly for Spectas. Actually we’re not supposed to have anything digital in the

Cell – we’d be evicted as soon as you could say iPhone. But we begged and begged and the elders said CDs were just about okay. No link with the Gnosys world, see? So we jam with CDs, and I kind of dig it. I like holding the music in my hand, having an actual, real thing in my hand. That’s rare these days – experiencing something real. We scav all our discs from what was once Foyle’s on Charing Cross Road, where a few racks of CDs gather dust among the shelves of rotting books.

Once the three of us have agreed on a song – never an easy task – we load the CDs into our Walkies. Then it’s time to get our Roxi disps out and do the deed.

Roxi – Retinal Oxygenating Xanthic Isopentyl if you want to be a geek about it – is a gas. Inhale it and it helps you breathe when you’re up above. It temporarily coats your lungs and throat in this protective chemical film that stops them getting clogged up with all the shit that’s in the air. It comes in black pellets which you load into blue plastic dispensers. We’re told that London is one of the most polluted cities in the world, and it definitely feels like it when you get back down into the Cell after scavving too long. One pellet equals roughly one hour. Any longer and your spit looks like liquid tar and you nearly cough your lungs out of your chest. Nobody gives a shit about pollution now though. Why would they, when most of the world lives in hermetically sealed boxes?

We’re between the devil and the deep blue sea, I always think to myself. Log in and live forever without any freedom whilst your brain turns to mush, or become one of us and almost certainly die from breathing in the poisonous atmosphere, but live out your days in the real world.

It’s how my mum died – from the bad air – when I was eight years old. When we first started living in the Cell she went back to her old job as a singer in an underground music hall in Soho. It was all she could get. Even back then, in the early days of the Upload, no one was employing Offliners.

Everyone told her not to – that she was asking for trouble – but I guess coming from where we came from, from the life we had before, she couldn’t bear it without some money to buy nice things now and again. When she managed to get peppermint tea, her own special treat, she’d hoard it in a tin and have about one cup a month. By ‘nice’ I’m talking like bread and pasta, or cocoa to make chocolate water, which is still, to this day, the sweetest thing that’s ever passed my lips. Those are our luxuries today.

When they found the tumour it was the size of a tennis ball and getting worse every day. Yottam Yellowfinch, our doctor in the Cell, gave her two weeks to live. She saw the month out – it was May – but was gone by the summer, which was her favourite season like it is mine. After she died, I asked Yottam whether anything could have been done to save her.

‘She loved you enough to kill herself for you to be happy. That’s what counts.’ I think it was kind of a harsh thing to say to an eight-year-old. I thought it was my fault. But once I started leaving the Cell on scav, I figured it all out pretty quick.

The production and supply of Roxi is controlled and rationed by the UN, in conjunction with Gnosys, the megacorp that provides Perspecta, the virtual reality in which most people now exist. We Offliners are only entitled to two Roxi pellets per week, maximum. I’m sure they’d much sooner give us no Roxi whatsoever and just let us suffocate. But the UN couldn’t be seen to publically condone genocide, could they?

There is a black market in Roxi, of course, but it’s a murderous business. Roxi runners are notoriously untrustworthy, and notoriously prone to ending up dead in some old dumpster. Gnosys hates them and everyone else envies them. So we can never be sure of our supply.

After my mum died, Ursula Stillspeare brought me a huge box full of pellets. She said Mum had never used them and so now they belonged to me. That’s when I got it; that’s when I understood what she had done.

Every time she had left the Cell, whether on scav or to go and earn a bit of spare cash at Peter’s, she had gone out naked, unprotected. Instead of taking the meds, she’d been saving them up for me. She always said she wanted me to see more of the world, to go up above and experience it. I suppose she thought she’d just take the chance – Hey, what’s the worst that could happen? Well, Mum, what happened was I lost you but gained a lifetime’s supply of . . . perspective.

I use the drug just as she intended – to allow me (and my two best friends) the freedom to be up in the world as much as possible . . . having as much fun as possible.

Here’s to you, Mum. Here’s to the Champagne Supernova.